History of the church building from its foundation

Although 1190 is regarded as the date when the present church building was founded, Jesus Christ had been worshipped in the hamlet of Sarratt long before then, probably on the same site.

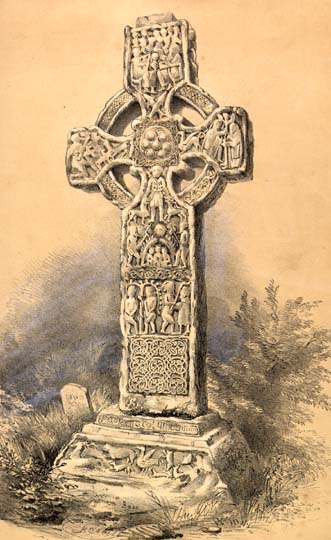

Most Norman brick and stone churches replaced smaller wooden Saxon field-churches or chapels, without leaving trace of the latter, and there is no reason to suppose that Sarratt was an exception (there is a report of 1866 suggesting that a church was erected in the 11th century). Moreover, the site, within the cluster of domestic dwellings that comprised the hamlet, was a prominent ridge position and the name `Holy Cross` could well indicate that originally a cross stood there as the first public sign of a Christian presence. It was common practice in England from about 800 to erect a cro ss as a high landmark, manorial boundary, or place of worship. Not only is the Sarratt site very close to a manorial and county boundary but also is said to have once been a focus for pagan worship; if so, a cross could have represented a Christian claim to the ground. The area around a cross was a place of sanctity where travelling priests or monks would teach, celebrate mass and baptise converts.

ss as a high landmark, manorial boundary, or place of worship. Not only is the Sarratt site very close to a manorial and county boundary but also is said to have once been a focus for pagan worship; if so, a cross could have represented a Christian claim to the ground. The area around a cross was a place of sanctity where travelling priests or monks would teach, celebrate mass and baptise converts.

Alternatively, the name of Holy Cross might not have been applied until the Norman church was built, influenced possibly by the prominent cross on Crusaders` uniforms in their popular struggles against Islam, for it was in July 1190 that Richard I set out on the 3rd crusade, one that fired the nation`s imagination more than any other.

The likelihood of there having been a Saxon cross and/or chapel derives from the fact that Christianity had been established in the west of the county for about 100 years before the hamlet was first settled in the 8th century. Accordingly people needed a local place of worship. Kings of Mercia had granted to St Albans Monastery a number of manors - including Sarratt in 796 - covering what then was a densely forested area. In about 948 the first three `parish districts` on the monastery`s estate were created, that nearest to Sarratt being St Michael`s, just outside St Albans.

The three parish churches depended on the monastery and were served by monks, some travelling round the parishes ministering to isolated populations such as Sarratt, and conducting services. Although monks must have been active earlier, the first reference to them in Sarratt is 1100, with a cell, founded by the monastery, known to have existed by about 1150. A cell was a monk`s base: a small, rough structure typically made of branches and trees wattled together.

It was not until about 1050 that the monastery authorised a systematic clearance of the forest. A short time later William I stipulated that a church must be built in every place with a population of at least 100. Although Sarratt was not included in the Domesday Book of 1087 settlement generally increased and early in the 12th century the district of St Michael`s was sub-divided. New parishes in Rickmansworth and Watford were created, with Sarratt and its environs probably part of the latter. The 11th and 12th centuries were a time of intensive building of churches, usually by a lay person and typically adjacent to a manor house.

It is not known when Sarratt became an ecclesiastical parish, though its manor was one of those that comprised the Liberty of St Albans, set up in 1161 by papal statute. In 1163 the abbot, who was a bishop with the right to appoint the archdeacon of St Albans, was exempted with his dependent manors from control by the diocesan bishop, by then residing in Lincoln.

Soon, Sarratt had its own permanent church building, probably built on his own land by a lord,  perhaps living in neighbouring Goldingtons, and given to the abbey as a sign of the new spirit of the age. It was an unpretentious cruciform building, with only a small chancel and nave, lacking foundations and a tower, although probably there would have been a tiny wooden turret containing a single bell to drive away devils and summon the people to service. A permanent church enabled Sarratt to become a separate parish, although there was no correlation between parochial and manorial boundaries.

perhaps living in neighbouring Goldingtons, and given to the abbey as a sign of the new spirit of the age. It was an unpretentious cruciform building, with only a small chancel and nave, lacking foundations and a tower, although probably there would have been a tiny wooden turret containing a single bell to drive away devils and summon the people to service. A permanent church enabled Sarratt to become a separate parish, although there was no correlation between parochial and manorial boundaries.

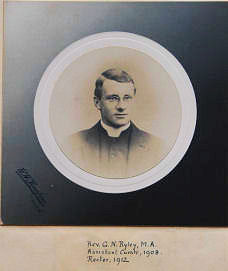

The present church building`s foundation date of 1190 derives from a leaflet by Gilbert Ryley, a former rector. In it he mentions the lord of the manor `about 1190 erecting a  house of prayer.` Compatible with this is the Victoria History of Hertfordshire which states that `there is nothing in the architectural features to suggest a date earlier than the last decade of the 12th century, to which time... the main part of the fabric seems to belong`. That such a comparatively large church should be built for the small community is unremarkable: agriculture had prospered during the 12th century and God was a dominant influence in people`s lives.

house of prayer.` Compatible with this is the Victoria History of Hertfordshire which states that `there is nothing in the architectural features to suggest a date earlier than the last decade of the 12th century, to which time... the main part of the fabric seems to belong`. That such a comparatively large church should be built for the small community is unremarkable: agriculture had prospered during the 12th century and God was a dominant influence in people`s lives.

Much of the historical material included in these sections has been obtained from: Sarratt: Historical Aspects of a Parish and its Church, published in 1990.

Other sources include the Victoria County History of Hertfordshire; A History of Hertfordshire by John Edwin Cussans, 1870; Social History of England by Asa Briggs; and The History and Antquities of the County of Hertford by Clutterbuck.

More detailed information may be found here.

William John Villiers Surtees and Charles Graham: two honest lads and hale. The Gentleman’s Magazine of December, 1832 reported a tragic accident that had recently happened in Oxford: Drowned in the Isis, aged 19, Mr William John Villiers Surtees, commoner of Exeter College, son of William Villiers Surtees Esq. of Devonshire Place, London; and Mr. Charles Graham, commoner of Trinity College, son of a clergyman of Kent. A memorial to one of the young men is on the wall of the Church of the Holy Cross in Sarratt, Hertfordshire. It reads: Sacred to the memory of William John Villiers Surtees, who was accidentally drowned November 29th 1832, in the 19th year of his age. The memorial will have been commissioned by his distraught parents, William Villiers and Harriet Surtees. His father was a barrister and private secretary to the lord Chancellor; his mother the daughter of a barrister. William John Villiers was the eldest of their five children. A similar memorial on the wall of the church of St. Mary Magdalen, Oxford, is dedicated to his friend: Sacred to the memory of Charles Graham of Trinity College in the University. Only son of the Revd. Charles Graham of Pelham, Kent, and Elizabeth his wife. He died on the 29th day of November, 1832, in the 20th year of his age. In the crypt beneath are deposited his mortal remains. Charles Graham’s father, the ‘clergyman of Kent’ was the Revd. Charles Clark Graham, the vicar of the church of All Saints, Petham, near Canterbury. What the two friends were doing on the Isis that day that caused them both to drown is as yet undiscovered. It seems to have been some sort of accident. They clearly drowned, and did not die as a result of physical injuries per se, of the kind caused by contact with a swiftly moving vessel; though the swirling water caused by such a craft could possibly have played a part. What is certain is that the deaths of these young men was keenly felt by their friends. One of these friends, particularly of Surtees, was Francis Orpen Morris (1810-1893) who was at Worcester College at the time. He was to become a noted parson-naturalist who in later life published widely on a variety of subjects. He is remembered as the author of a popular, six-volume work on British birds, referred to today simply as ‘Morris’s birds’ and the equally popular ‘British Butterflies’ and ‘British Moths’, all of which went through many editions and are sought after today. Surtees was a friend of Morris’s younger brother, Frederick, and became a close friend of Morris when he went to Oxford in 1831. Frederick Morris and Surtees both attended Sherborne School in Dorset. Not far from Sherborne is the village of Glanville’s Wootton. The manor house there was the home of the famous entomologist James Charles Dale, (1791-1872) with whom F.O. Morris - as he is always known - corresponded. Morris was most eager to cultivate a friendship with the older man, having become an enthusiastic, though not overly adept, entomologist himself, and was keen to assemble a collection of insects. He first wrote to Dale in 1829 before he went to Oxford (the family lived at Charmouth) to ask if he could view his insect cabinet; it was well known that Dale had one of the finest collections in Britain. He was duly invited, and was much impressed. Morris then wrote regularly to Dale from Oxford to ask for advice and specimens. Two years later, in September, 1831, he wrote on behalf of his brother: (I) ‘write to ask you if you would allow him and his schoolfellow Surtees (a nephew of Lord Eldons) to see your collection on the day of the Coronation - if convenient to you will you let him know’. Surtees had left Sherborne school and gone up to Oxford in September, 1831, but was obviously in touch with his younger schoolfriend (he was two years older than Frederick) and it was probably through Frederick that Surtees came under Morris’s wing - which he seems to have done - upon his arrival. Morris had been there for two years. Probably Morris told Surtees that Dale’s collection was 2 a must-see if he was interested in entomology, and suggested that Frederick, still at Sherborne school, was best placed to arrange it; and duly wrote on his behalf to Dale. Morris was a great manipulator, evidence for which is legion in his correspondence but outside the scope of this short narrative. Frederick and Surtees duly met, presumably at Sherborne, went to Glanville’s Wootton and thoroughly enjoyed their visit. They were no doubt welcomed by Dale, and perhaps his parents too. They were still very much in charge of the manor house and its lands, and Dale, the only son and forty years old by this time, as yet unmarried, spent most of his time on his entomological pursuits. He was indulged in this, perhaps not always willingly, by his parents, as all anyone had to do to gain their son’s invitation to the house was to express an interest in entomology. The two young men would have been given a genial welcome by the famous entomologist, and Surtees would hardly not have been impressed by Dale’s collection. That Morris thought Dale would have been interested in Surtees’ subsequent career is indicated by the tone of a letter that he wrote to him after Surtees’ death just over a year later. Morris assumed that Dale would remember him well and would wish to know of the reaction in Oxford to the tragedy. This is his letter, written in early December 1832: Dear Dale, In great haste I write you a few lines. Poor Surtees - I send you as a relic the last words that he wrote in my rooms, by his list - Kay says that his Lepid are so bad that you may send all I have marked off to the Ashmolean - will you ask Curtis to put my name down as a subscriber to his book, I will order it through Mr Soham bookseller at Oxford - I have the last number but see nothing of Oxycera in it - I heard from Frederick and Beverley at Sherborne by Fanshawe yesterday who has come up to enter at Corpus - Surtees brother is coming up to the Coll next term - they have given over all his things to his friends at Oxford, that they might take nothing home to increase the grief of his family, he is taken down into Hertfordshire - Graham was buried in Oxford - I suppose you have heard particulars. I have no room for any, but I can assure you I have never been more afflicted or felt anything more, it has altogether been one of the most melancholy events I know of and seems to have been universally felt so. Believe me Dear Dale yours most truly FOMorris The ‘list’ that Surtees was writing was of his desiderata for his insects collection. ‘Lepid’ refers to Surtees’ collection of Lepidoptera - butterflies and moths - which was not in good condition. Curtis is the entomologist John Curtis, (1791-62), a great friend of Dale and author of ‘British Entomology’, and ‘Oxycera’ an insect which Morris had sent to him to be figured in his book. It is unfortunate that Morris does not give the particulars of the death of the two young men, supposing that Dale had already heard details. But clearly he, and many others, were shocked and horrified at the event. Surtees seems to have been a popular young man. Many years later Morris’s son, M.C.F. Morris, was to write a biography of his father. He quoted him as saying that the sudden death in 1853 of an admired friend and colleague the day after he sat next to him at a meeting affected him deeply, and ‘On one other occasion only in my life, when another valued friend, W.J.V. Surtees, was most unfortunately drowned at Oxford, have I ever had such as shock…’ Much less is known about Charles Graham. He had two sisters, Jane Mary (b.1810) and Frances Margaret (b.1815). His father died, aged 60, in 1837. We know that he was Surtees’ friend, that he drowned, and that his parents decided to have his remains interred in a place he must have loved rather than have them taken back to his birthplace. Not much more is known of W.J.V. Surtees; he was a scholar at Sherborne School, he was interested in entomology, he had made a little collection of butterflies (though his specimens were in an indifferent state of preservation), he was a popular undergraduate, and his family was so distraught at his death that they could not bear to have his belongings brought home. His brother distributed them amongst his friends. If it were not for F.O. Morris even these scraps would have been lost to history. 3 The memorial on the wall of Holy Cross church says little, but there is a poignant story there. As there is in the memorial in St. Mary Magdalen, though it is a much shorter one. The story - the life and death - of these two unfortunate young men still remains something of a mystery. But the two friends deserve a little more than dusty plaques on the walls of churches, unacknowledged, names long forgotten, existing only as a reference to an ancestor on genealogical websites. There is no evidence that F.O. Morris ever went to Ludlow - though he was at school at Bromsgrove, thirty miles away - he may well have approved of these lines from A.E.Housman’s A Shropshire Lad as an appropriate memory of Surtees and Graham:: When last I came to Ludlow, amidst the moonlight pale, Two friends kept pace beside me, two honest lads and hale. © Tony French. January 2022. Selected Bibliography Extracts from letters are courtesy of the Oxford Museum of Natural History: Dale Archive, F. O. Morris correspondence JCD/C/Morris/001-156 ANONYMOUS 1832. The Gentleman’s Magazine and Historical Chronicle, Vol. 102. London. BURKE, J. 1838. A Genealogical and Historical History of the Commoners of Great Britain. Vol.4. London. DALE, C.W. 1878. The History of Glanville’s Wootton in the County of Dorset. London. HOUSMAN, A.E. 1940. A Shropshire Lad. With Wood Engravings by Agnes Miller Parker. London MORRIS, M.C.F. 1897. Francis Orpen Morris: A Memoir. 1897. London.3 PICK, B. PICKERING 1950. The Sherborne Register. 4th. Ed. Winchester.